In Brief

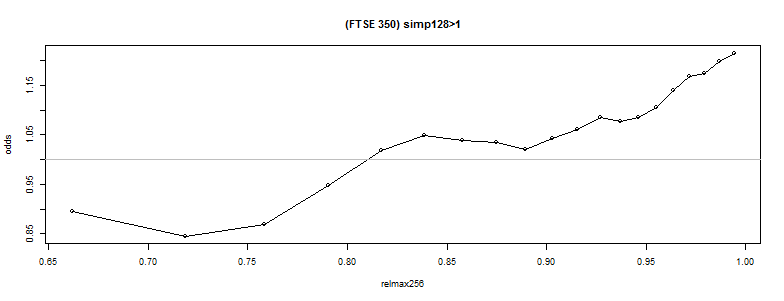

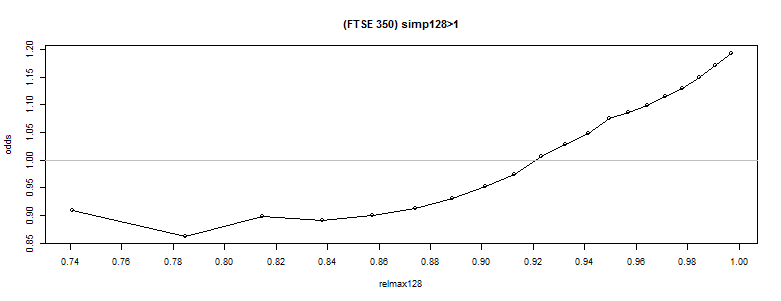

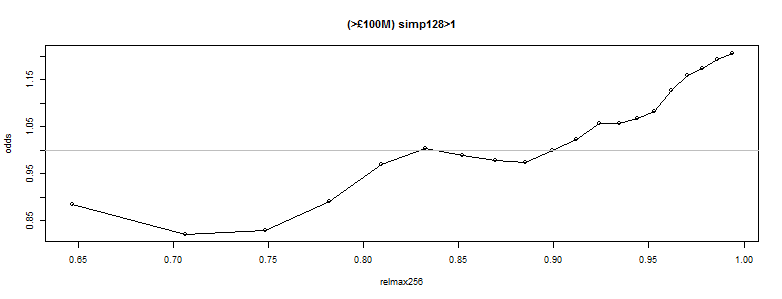

An investing screen based on buying stocks that are close to their 52 week high (and/or selling stocks that are close to their 52 week lows), particularly in industries whose stock prices are close to their 52 week highs (or lows). Similar to other forms of momentum investing, this appears to work because investors tend to under-react to positive (or negative) information about those kinds of stocks.

Background

Every day, financials newspapers like the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times, and the South China Morning Post publish lists of stocks whose prices have attained new 52-week highs and lows. Many investors approach such a list with trepidation, understandably assuming that this may mean that stocks prices are approaching “nosebleed” territory. However, recent research suggests that this may be exactly the wrong conclusion, perhaps precisely because everyone else is thinking the same thing. As has been discussed elsewhere, academic researchers have found that stock prices look to have "momentum". More recently, work by researchers George and Hwang published in the Journal of Finance has shown that the closer a stock's current price is to its 52-week high, the stronger that stock's performance in the subsequent period. They conclude that “price levels are more important determinants of momentum effects than are past price changes”. In subsequent work this year, they also found an industry level 52 week high effect which was even more pronounced.

Why Does it Work?

George and Hwang surmise that investors use the 52- week high as an “anchor” against which they value stocks, thus they tend to be reluctant to buy a stock as it nears this point regardless of new positive information. As a result, investors underreact when stock prices approach the 52-week high, and consequently, contrary to most investors' expectations, stocks near their 52-week highs tend to be systematically undervalued. Finally, when information prevails and the 52 week high is broken, the market “wakes up” and prices see excess gains. Similarly, when bad news pushes a stock’s price far from its 52-Week High, traders are initially unwilling to sell the stock at prices that are as low as the information implies.

They conclude:

“Traders’ reluctance to revise their priors is price-level dependent. The greatest reluctance is at pricelevels nearest and farthest from the stock’s 52-week high. At prices that are neither near nor far…